When Does Someone’s Confidence Need a Check-In?

I remember a time way early in my career when I was given my first big software project. It involved a completely unfamiliar framework and a set of requirements that felt less like a blueprint and more like a collection of…idk, something confusing (I’m looking at you Graph ML).

I sat at my desk, paralyzed. I wanted to look competent, so I avoided asking the most foundational questions I desperately needed answers to. Every step felt like a potential disaster, and I spent hours staring at the screen, effectively doing nothing because I was trapped in a cycle of self-doubt. That fear of asking questions, born from a lack of confidence, ended up costing me (and the project) valuable time.

This personal memory highlights a fundamental truth about learning, work, and leadership: everyone needs support and feedback. However, I’ve noticed that the type and amount of support an individual requires are highly correlated with where they fall on a confidence spectrum. It's not a simple one-sided curve; it’s a dynamic relationship where both too little and too much confidence can demand a heavy investment of a supervisor’s time.

The Confidence-Shy Side: The Need for Hand-Holding

On one end of the spectrum, we find individuals who have very little confidence in their own abilities, especially in a new or unfamiliar setting. These are often new hires, people transitioning to a new role, or someone simply faced with a task outside their established comfort zone.

My personal experience at the start of that software project is a good example. These individuals are prone to asking a seemingly endless stream of clarifying questions, sometimes to the point of paralysis by analysis. They require a lot of hand-holding, needing clear, step-by-step guidance and frequent reassurance that they are doing the right thing.

They aren't trying to be difficult; they are simply trying to mitigate risk because they lack the internal framework of experience and confidence to proceed independently. For a manager or leader, the time investment here is high because you are responsible for building their foundation, not just guiding their steps. You must provide the missing confidence and act as a constant, easily accessible resource.

The Confidence-Full Side: Assumptions as Obstacles

On the opposite side, we have people overflowing with confidence. These individuals are ready to jump into any project immediately. Their self-assurance is a powerful initial asset—they are decisive and not afraid to start working. But this level of confidence can be a sneaky obstacle that creates its own need for intensive feedback.

Their self-assurance often leads them to make a cascade of unverified assumptions about the requirements, scope, or desired outcome. They are so confident in their ability to solve the problem that they mistakenly believe they already understand the nature of the problem itself.

Imagine I ask a person on this side of the spectrum to "get me a dog house." Based on their confidence, they might immediately drive to a lumber yard, buy wood, nails, and tools, and spend hours building a large, sturdy structure. They'd feel great about their initiative, but they missed asking a few crucial questions:

- What is the budget? (Did they spend three times what I planned?)

- Is this for a Great Dane or a chihuahua? (Size matters!)

- Is this an indoor or outdoor house?

- Can I just buy a pre-made plastic kennel? (Are carpentry skills even necessary?)

And here's the kicker: I might have just wanted a small, decorative Barbie Dog House for my collection. Their confidence got in the way of asking clarifying questions, leading to a massive scope creep, wasted effort, and a result that doesn't align with my actual need. For the supervisor, this is time spent revising and course-correcting work that was done confidently but incorrectly.

The Sweet Spot

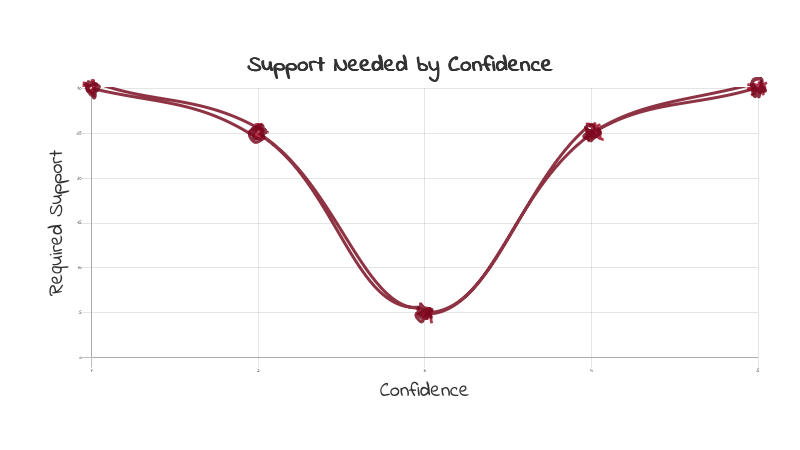

If we visualize this relationship on a graph, the required support is high at both the low-confidence (left) and high-confidence (right) extremes. The required support dips lowest in the middle.

The ideal space is where an individual has balanced confidence. They have the self-assurance to tackle unfamiliar territory—to jump in and start—but also the self-awareness and humility to pause and ask the right clarifying questions when they hit an area of genuine uncertainty.

This balanced approach allows them to learn quickly in an unfamiliar place because they have the confidence to experiment, but they mitigate risk by checking their critical assumptions. They ask, "Before I build this, what is the budget, and what is the maximum size?" This simple act of questioning saves hours of future rework.

Sparking the Discussion

Confidence is a wonderful asset, but as with anything, an extreme on either side requires extra energy and effort from those around you. The truly efficient worker is the one who confidently proceeds, but humbly pauses to ask for clarification on the requirements, not just the how-to.

I'm curious to hear your thoughts. Have you observed this confidence-to-support dynamic in your own work or team? What is one simple question you’ve learned to ask early in a project that prevents a major rework down the line?

Sources and Further Reading

- How to give feedback - HBR

- Paradox of Confidence in Leadership - MoreThanDigitial

- Study on Figuring Out One’s Own Confidence - ResearchGate

- Study on Self-Efficacy - PyscNet

- Self-efficacy, Motivation, and Performance - Taylor & Francis

- Are You Overconfident and Underconfident at the Same Time? - Psychology Today

- Put Your Ego Aside - Hackernoon

Comments ()