How I Left YouTube

I remember sitting down in a meeting room hearing the results of my third try at promo cycle trying to get from an L4 to an L5. I helped launch/lead features on YouTube, I led teams, I designed and implemented systems that were still in use to that day by many people, people all across the org knew me and said I was indispensable to the company and were surprised that I wasn't already at an L5/6 level. The results of that meeting? The same from the previous promotion decisions; “it’s unfortunately a no. You don’t have enough impact.”

That Tuesday afternoon realization kicked off a grueling, educational, and emotionally taxing journey: leaving a "dream job" to find out what I was actually worth in the open market.

The Mathematics of Leveling

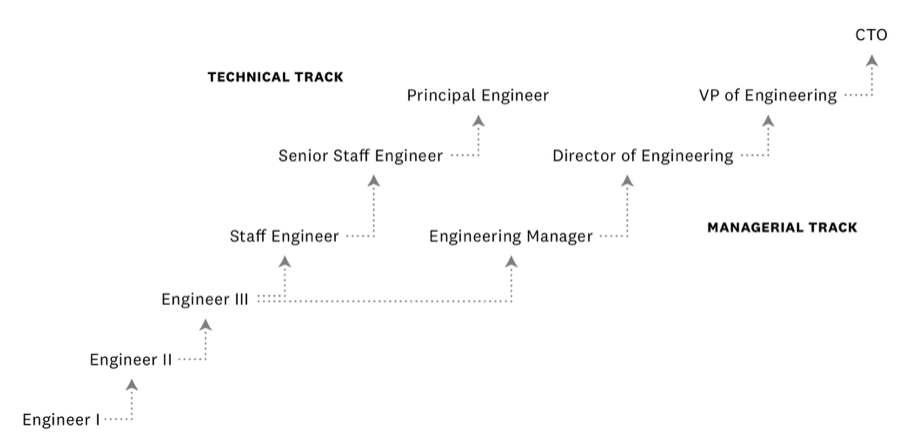

In the software engineering world, we exist on a ladder. We call this ”Leveling”.

For those outside the tech industry, imagine the military. You have Lieutenants, Captains, Majors, and Generals. In tech, these are usually denoted as L3 (Entry/Junior), L4 (Mid), L5 (Senior), and L6 (Staff). L1/2 are saved for contractors or interns. After these denominations, one usually switches to a director or someone on the Leadership team. Your level dictates your salary, your stock grants, and most importantly, the scope of problems you are allowed to solve.

I found myself in a situation common to many engineers at large organizations. I was operating at a “Senior” or “Staff" level (architecting systems and roadmaps rather than just writing the code and tracking bugs), but my official title and compensation were stuck at just above junior level.

I faced a choice: continue to do way more work to prove myself for the lottery that is the promo cycle or leave to find a company that would recognize my output immediately. I chose the latter. And I decided to attempt a "double level" jump during my interviews (L4 to L6). I didn't just want a lateral move; I wanted the title that matched the work I was already doing.

The Double Life of the Employed Candidate

Hunting for a job is a full-time occupation. Doing so while maintaining high performance at a demanding job like YouTube is a recipe for cognitive fracture.

The strain comes from context switching. From 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM, I had to care deeply about our quarterly goals and production stability. Then, from 6:00 PM to midnight, I had to care about inverting binary trees and system architecture design.

I recall taking "calls" in my car, taking vacation days to practice and do interviews, tethering my laptop to my phone's hotspot to solve coding challenges while squatting in a coffee shop down the street from the office. This duality is exhausting. It forces you to lie by omission to people you respect. You can't tell your team, "I can't take that ticket because I need to study dynamic programming." You just have to work faster.

Navigating the NDA Minefield

One of the most complex hurdles in this cycle was proving I was capable of that "double level" jump without breaking Non-Disclosure Agreements (NDAs).

When you work at a place like YouTube, the scale of the problems you solve is the primary selling point. However, the specifics of how you solved them are often trade secrets.

Here is the strategy I developed: Abstract the mechanism, not the metric.

I couldn't tell interviewers exactly how a specific proprietary algorithm worked. Instead, I focused on the agnostic engineering principles.

- Don't say: "I tweaked the YouTube watch-time algorithm using X variable."

- Do say: "I optimized a high-throughput distributed system to prioritize user retention metrics, reducing latency by 150ms through a custom caching layer."

It shows you understand the systems (which is transferable knowledge) rather than just the product (which stays at the old company). If you are ever in this position, focus on the scale of the data and the architectural patterns you used (like Microservices or Event-Driven Architecture) rather than the feature itself. In the end, it also helped me connect with external technologies and lingo better!

The Elephant in the Room...

Most interviewers asked me the question that people assume is the hardest to answer... "describe why you are not already an L5/6". And honestly, this was the easiest part. People understood the problems with promos at Google/YouTube, but also this situation. The problem of "doing more work and not getting compensated" is pretty well-known.

What was unique was how long it took me to decide to leave. And I had to highlight the incredibly talented team I worked with and the amazing managers that taught me so much. There is so much value in knowing and feeling that the people around you care about you and want to build amazing things with you.

The Thirteen-Interview Marathon

The most alarming trend I analyzed during this cycle is the inflation of the interview loop.

At one prominent tech company, I underwent 13 separate interviews for a single role. This included initial screens, coding rounds, system design rounds, behavioral checks, and meetings with cross-functional partners.

From a critical perspective, this signals organizational dysfunction. If a company requires 13 people to sign off on a hire, it suggests they operate on a consensus-based model that stifles autonomy. It implies a fear of making mistakes that outweighs the desire for talent.

When I analyze the data from my own process, the companies with 5 to 8 rounds had the clearest internal culture. They knew what they wanted. The company with 13 rounds was fishing for a reason to say "no” (which some ultimately told me).

The Final Conversation

We often hear that "people leave managers, not jobs." But sometimes, people leave jobs despite loving their managers.

My final conversation with my manager was heart-wrenching. I had prepared a script, anticipating a counter-offer or a guilt trip. Instead, I was met with soft and understanding empathy.

I explained that my growth curve had flattened. I wasn't leaving because the team failed me; I was leaving because I had outgrown the pot I was planted in. Staying would have required me to stagnate to fit the available space. I needed to leave to see what I was capable of. And he listened to every word.

I walked out of the meeting feeling incredibly bittersweet, with tears ready to fall. He knew my talent, he knew how hard I worked, and he still was incredibly supportive while I said I was leaving.

This is a hard lesson for both employees and leaders: Retention has a ceiling. Sometimes, the best thing a manager can do for that high-performer is to wish them luck as they walk out the door. It wasn't his fault I wasn't promoted to the level I wanted—he was fighting the same bureaucratic machine I was.

The Takeaway

Leaving a recognizable brand like Google/YouTube is frightening. You lose the immediate validation that comes with the name on your resume. But careers are long, and comfort is the enemy of progress.

If you feel like you are solving problems two levels above your pay grade, and the only reward you get is more work, it is time to test the market. The interview fatigue is real, and the conversations are hard, but the clarity you gain on your own value is worth the struggle.

I’m curious about your experiences with career stagnation. Have you ever felt like you were "acting" at a higher level than your title? How did you handle the conversation with your leadership?

Please share your stories in the comments below.

Links and Resources

- Software Engineering Levels: levels.fyi (Excellent resource for comparing titles and compensation across big tech).

- Github: Career Ladder (detailed guide on how Github views levels; and I personally like their view)

- System Design Interview Guide: System Design Primer on GitHub

- Navigating NDAs: Harvard Business Review: Non-Disclosure Agreements

Comments ()