How to Save Money with Big Data: Finding Matches (Part 3)

Imagine a search engine receiving millions of queries a second. Before sending an expensive request to a back-end service, we need a lightning-fast check to see if we've already cached the answer or if the topic is even relevant, such as determining if a topic is breaking news. Or perhaps we need to find all near-duplicate documents or videos in a massive collection. This is where the last set of Probabilistic Data Structures shine, helping us with Membership (is it in the set?) and Similarity (how alike are these two things?).

Membership: The "No, Maybe" Answer

Membership queries are about quickly checking if an element (x) is present in a set (S).

The Bloom Filter

The Bloom Filter is probably the most well-known PDS. It's highly effective and is used in web caching, spam filtering, and database query optimization.

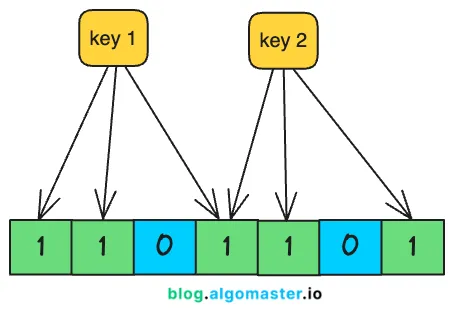

- Mechanism: A Bloom Filter uses a bit array of a fixed size (S) and a number of independent hash functions (k).

- Insertion: To add an element, we hash it with all k functions and set the corresponding bit in the array to '1'.

- Query: To check for an element's presence, we hash it again with all k functions. If all resulting bits are '1', the filter returns "maybe in set" (a positive). If any of the bits are '0', it returns "definitely not in set" (a negative).

- The False Positive: The key trade-off here is the possibility of a False Positive (saying "maybe in set" when it's actually not) due to a collision where other elements set all the required bits to '1'. However, a Bloom Filter never produces a False Negative. This property makes them invaluable for processes where we cannot afford to miss a positive hit, like checking for breaking news before sending a costly network request (RPC). Using a Bloom Filter in this scenario can result in massive resource savings, such as a 96% reduction in network space with a negligible error rate.

The Cuckoo Filter

A modern evolution of the Bloom Filter is the Cuckoo Filter. It is generally more space-efficient and has a crucial advantage: it allows for the deletion of elements, which Bloom Filters do not support.

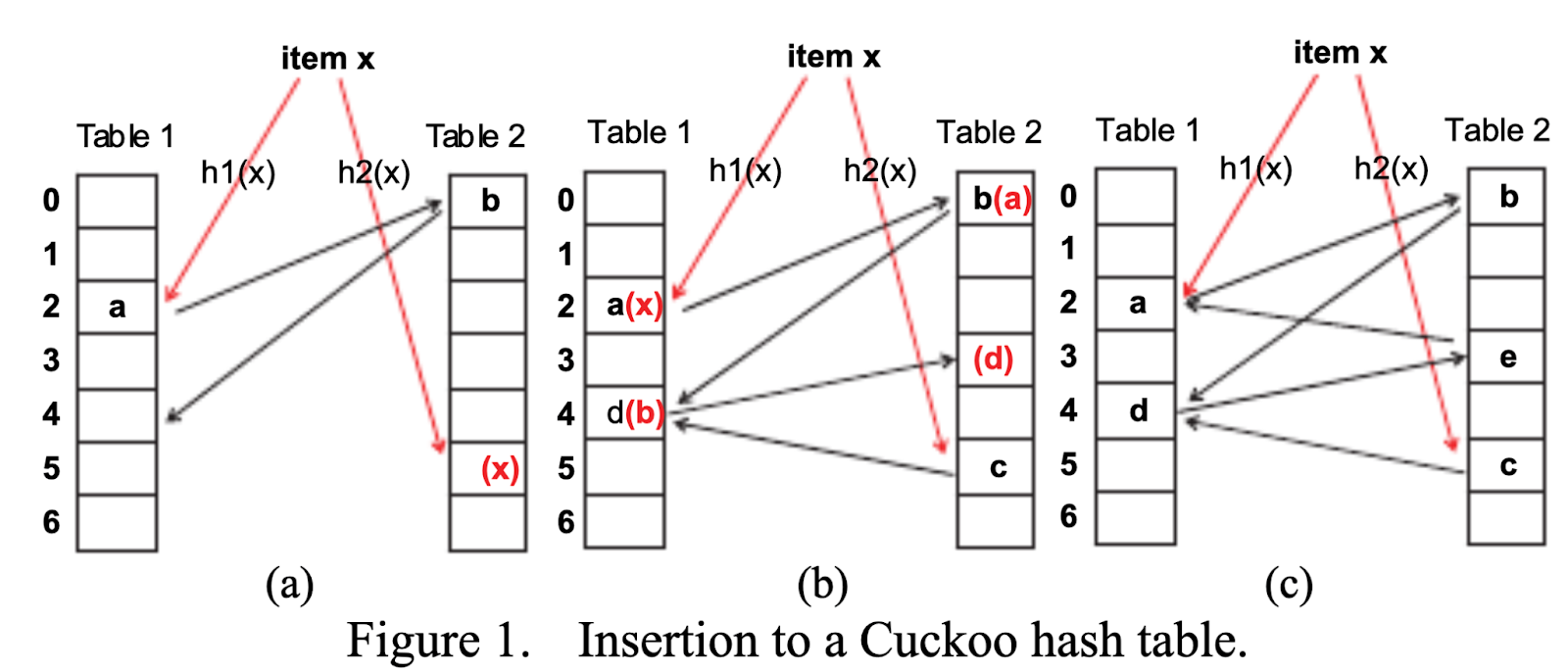

- Cuckoo Hashing: Each item is assigned two potential locations (or buckets) based on two different hash functions. If both locations are full upon insertion, the new item displaces an old item, which then "flies" to its own alternative location, continuing this process recursively until a free slot is found or a relocation limit is hit.

- Called Cuckoo because the cuckoo birds take over nests. So this displacement of values mimics how cuckoos nest.

Basically, there are only 2 places an element could be for every element. This allows for fast lookups and efficient use of space!

Similarity: Finding Close Matches

In large datasets, we often need to measure how similar two items are, such as finding near-duplicate web pages or highly related videos.

MinHash

MinHash is used to approximate the Jaccard Similarity (the size of the intersection divided by the size of the union) between two sets.

- Mechanism: It works by hashing all elements of a set multiple times (k times) and then simply keeping the minimum hash value for each hash function. This collection of k minimum values (the "MinHash fingerprint") becomes a compact, fixed-size representation of the original set. The probability that the MinHash fingerprints of two sets are equal is equivalent to their Jaccard Similarity. This allows us to compare two massive sets simply by comparing their small fingerprints.

SimHash

SimHash is an algorithm often used to detect near-duplicate documents, frequently relying on Hamming Distance (the number of differing bits in two binary strings) for a quick similarity check.

- Mechanism: It works by hashing the weighted features of a document (like the weighted words or n-grams), calculating the average of the bits across all hashes, and then taking the sign of the resulting vector to produce a compact final hash value. The similarity between two documents is then approximated by the Hamming Distance between their SimHash values.

These techniques move beyond exact matching to allow for fast, scalable nearest-neighbor searches, a necessity for creating large-scale recommendation graphs based on dense vectors (I’m looking at you vector based retrieval solutions!), where traditional tree-based searches suffer from the "Curse of Dimensionality".

The power of a probabilistic approach is clear: in an age of petabyte-scale data, the right approximation is often the only possible solution. How has the ability to get a "good enough" answer in real-time changed the way you approach software architecture or data analysis?

Final thing: Thank you for reading this series! I love PDS and the cleverness of their design is so fun. I hope you enjoyed these slightly more technical articles!

Comments ()