Rise of Liquid News: Formats for the User

I remember trying to make sense of a recent financial scandal last year. I had like ten tabs open on my browser: CNN, The New York Times, a few Substack newsletters, and a dense Wikipedia entry. Every single piece of information forced me to wade through the same three paragraphs of introductory fluff before getting to the new information. The "analysis" pieces were too long for my morning commute, and the "breaking news" alerts were too shallow to be useful.

I wasn't struggling with a lack of information; I was struggling with the rigidity of the container. The news were trapped in static blocks of text, written by someone who didn't know if I was driving, sitting at a desk, or holding a crying baby (or a chunky kitty in my case).

This friction is why I am interested in the concept of Object-Based Media (OBM). It is a shift that doesn't just change how we consume news. It changes what "news" actually is. We are moving toward a future where writers stop writing articles and start building knowledge graphs, leaving the actual storytelling to what the user needs.

Breaking Stories into Atomic Units

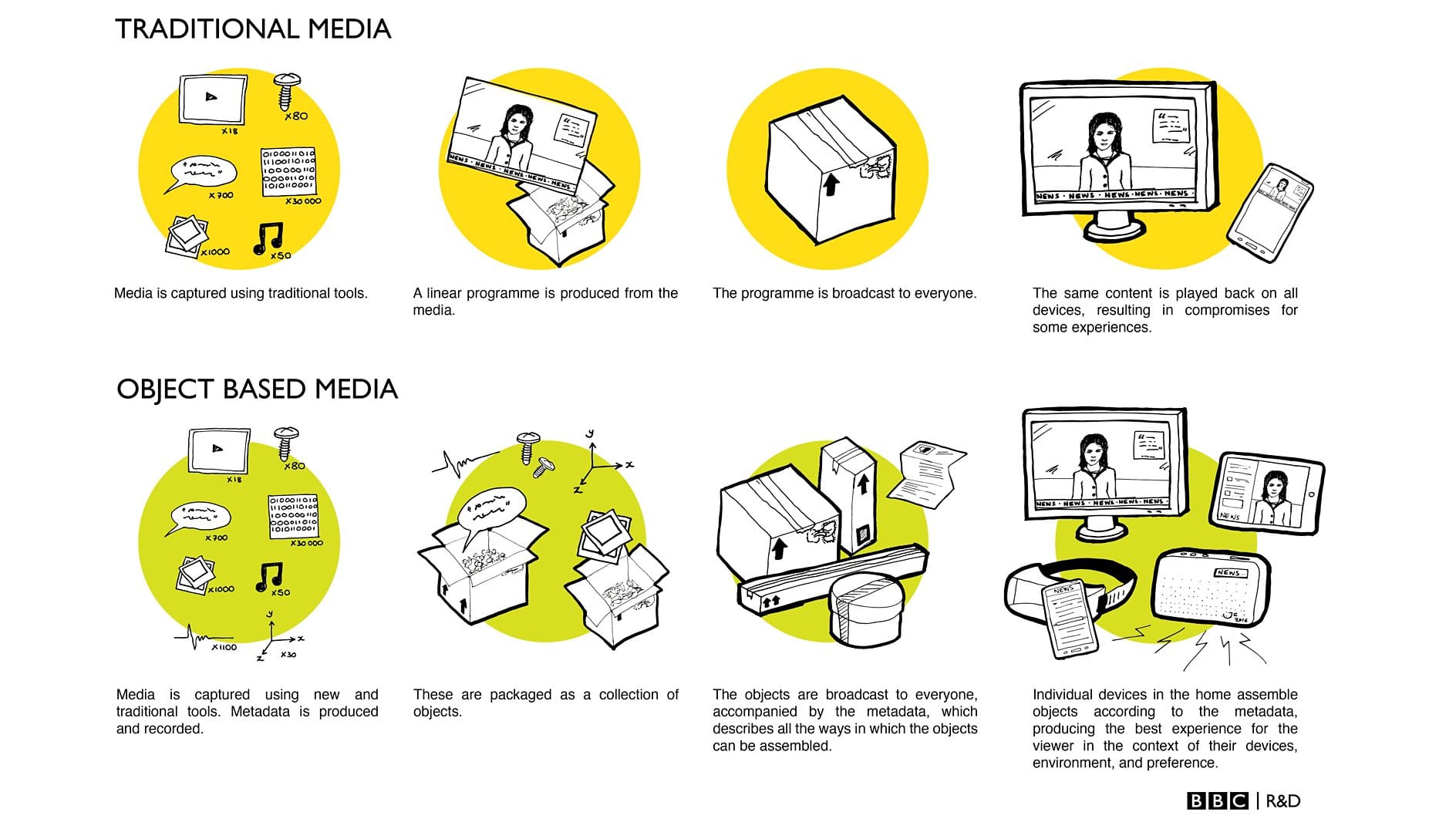

At its core, Object-Based Media is the practice of breaking a story down into its smallest "atomic" units. BBC R&D has been pioneering this concept, describing it not as a single video or article, but as a collection of assets (video clips, audio stems, text blocks, and data points) that can be reassembled on the fly.

Think of a traditional article like a pre-baked cake. You get what you get. If you hate raisins, you have to pick them out. Object-Based Media is more like a pantry of ingredients. If you want a cake, your device bakes a cake. If you’re diabetic, it bakes a sugar-free one. If you’re in a hurry, it just hands you a muffin.

In this model, a journalist doesn't sit down to "write a story." Instead, they input facts into a structured database:

- Entity A: The Senator

- Entity B: The Lobbyist

- Event: Meeting at 2:00 PM

- Evidence: Photo of the meeting

- Quote: "I did not inhale."

This collection of connected facts forms a Knowledge Graph. It is a web of relationships rather than a linear narrative.

Liquid Content: The Shape-Shifting News

Once the journalist has verified and uploaded these atomic units, the "Liquid Content" phase begins. This is where the magic happens on the user's side.

Imagine you have a personal AI news agent on your phone. It knows your context and your preferences.

- Scenario 1: The Commute. You get in your car. Your AI sees you are driving and have 20 minutes. It takes the knowledge graph of the scandal and renders it into a 15-minute audio podcast, focusing on the timeline of events.

- Scenario 2: The Deep Dive. Later that night, you are on your iPad. The same AI takes the exact same facts and renders a 3,000-word investigative feature with interactive charts, photos, and a timeline you can scroll through.

- Scenario 3: The Update. Two days later, a new fact is added to the graph. Your AI doesn't make you reread the story. It sends you a single notification: "Update: The Senator admitted to the meeting."

This solves the personalization issue that current algorithms get wrong. Right now, algorithms show you different stories based on what they think you like (often creating echo chambers). In an Object-Based future, we all get the same facts, but the format adapts to our mode of intake.

The Death of Spin?

This brings us to the most interesting ethical implication: Fact-checking the Graph.

Bias in journalism often hides in the prose. It’s in the adjectives, the tone, and the structure. A writer can bury a contradictory fact in the twelfth paragraph where no one reads it, or use emotional language to sway opinion.

If we take the "writing" out of the equation, the bias becomes harder to hide. When a journalist is building a knowledge graph, they are making explicit assertions about reality.

- Fact: Person A paid Person B.

- Source: Bank Record #123.

It is arguably easier to audit a database for contradictions than it is to police the nuance of human language. You can run automated logic checks on a graph. If the graph says "The Senator was in D.C." and "The Senator was in London" at the same time, the system flags the error immediately.

However, this shifts the "line of abuse." If the knowledge graph itself is poisoned—if a bad actor inserts a false relationship into the root data—then every rendering of that story, whether it’s a text article, a video summary, or an audio report, will be false. The battle for truth moves from the editorial desk to the database schema.

We will need new protocols for "Graph Integrity." We might see cryptographic signatures on specific facts (e.g., this photo was signed by the Reuters camera that took it; we might have actual use for blockchains!). We might have "Graph Auditors" instead of Copy Editors, whose entire job is to ensure the edges between nodes in the network are supported by evidence.

A New Role for the Writer

Does this mean the end of human creativity? I personally don't think so. It elevates the journalist from a "content churner" to a "truth architect.” And there are still columnists, opinion articles, editorials, and commentary that allows writers to spread their wings.

Right now, thousands of brilliant writers are wasting their time re-writing press releases or summarizing other people's reporting just to feed the SEO machine. In an OBM world, those writers are freed to do the actual work: finding the facts, verifying the sources, and capturing the interviews. The AI can handle the mundane task of turning those facts into sentences.

I want a future where I can trust the data implicitly, but choose the voice that delivers it. Maybe I want the facts of the economy delivered with the wit of Anthony Bourdain or the precision of a Walter Cronkite (RIP to both legends). The data remains pure; the delivery is a mask we can put on and take off at will.

This future is frightening to some because it surrenders the "art" of the article. But if the goal of journalism is the transfer of verified information from the ground to the public consciousness, Object-Based Media is a far more efficient engine than the printing press ever was.

Would you trust a news report generated by an AI if you could inspect the raw database of facts it was built from? Or do you need a human to connect the dots for you? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below.

- BBC R&D on Object-Based Media: BBC Research & Development

- Liquid Content Concepts: Lets Flo on Liquid Content

- Knowledge Graphs in Media: Gyrus AI on Media Search

- Fact Checking with Graphs: GraphCheck Research Paper

- Future of Data Journalism: Generative AI in the Newsroom

Comments ()