The Real Gap Between What We See and What We Know

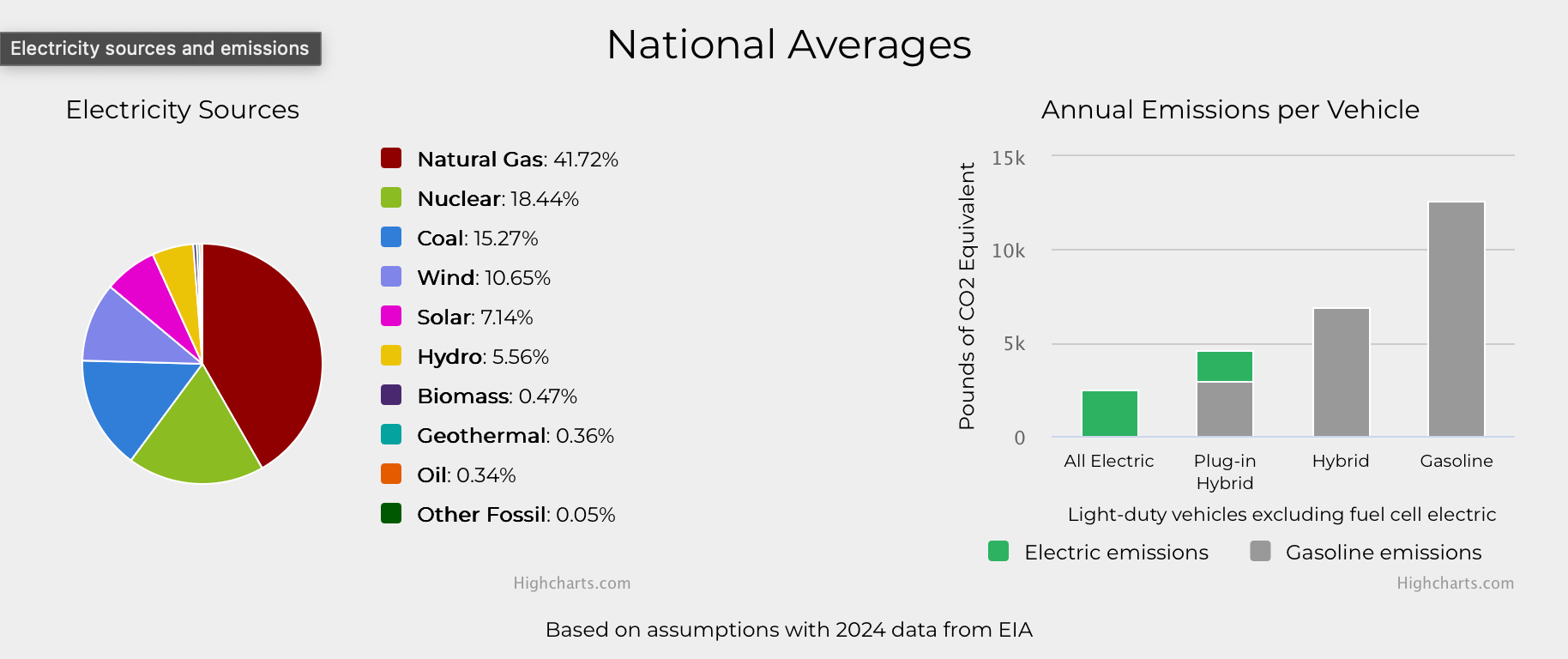

I recently found myself stuck in a debate that felt like running into a brick wall. A friend argued that electric vehicles (EVs) were actually worse for the environment than gas cars because, in their words, "you're just charging them with coal anyway." When I pulled up data showing that coal makes up less than 20% of our energy grid and that power plants are fundamentally more efficient than car engines, they shrugged it off (more interesting nuances could be found in this paper). It wasn't that they couldn't read the graph; it was that the data didn't fit the story they already believed.

This interaction made me realize something. We live in an era where information is everywhere, yet true awareness seems scarce. It is difficult to discuss new lunar discoveries with someone who doubts we ever landed on the moon, just as it is nearly impossible to discuss climate policy with someone who doesn't grasp the basics of the carbon cycle.

As someone deeply invested in how news and technology shape our reality, I’ve started wondering: How do we actually measure what the public knows? And more importantly, how do we bridge the gap between perception and reality?

The Yardstick of Awareness

Measuring public knowledge is trickier than just checking if people watch the news. In journalism and sociology, we often look at two different types of knowing: perceived knowledge and factual knowledge.

Perceived knowledge is how much you think you know. Factual knowledge is what you can actually demonstrate. The gap between these two is often where arguments happen.

For example, large-scale surveys like those from the Pew Research Center or Gallup are the traditional way we gauge this. They ask specific questions—"Does the Earth go around the Sun?" or "What percentage of our energy comes from fossil fuels?"—to create a baseline of scientific literacy.

But in the digital age, we have new tools. We can look at "search interest" via Google Trends to see if people are looking for answers or just looking for confirmation. We can use social listening tools to analyze the sentiment of conversations. If the volume of search traffic for "moon landing fake" spikes, we know that awareness of the actual Apollo missions is competing with a counter-narrative.

Why Facts Often Bounce Off

You might think the solution is simply to provide more facts. If people knew that coal usage has dropped to historic lows, surely they would change their minds about EVs?

Sociologists call this the Information Deficit Model. It assumes that public skepticism is caused by a lack of information, and that filling the "deficit" with data will fix the problem.

Unfortunately, it rarely works that way.

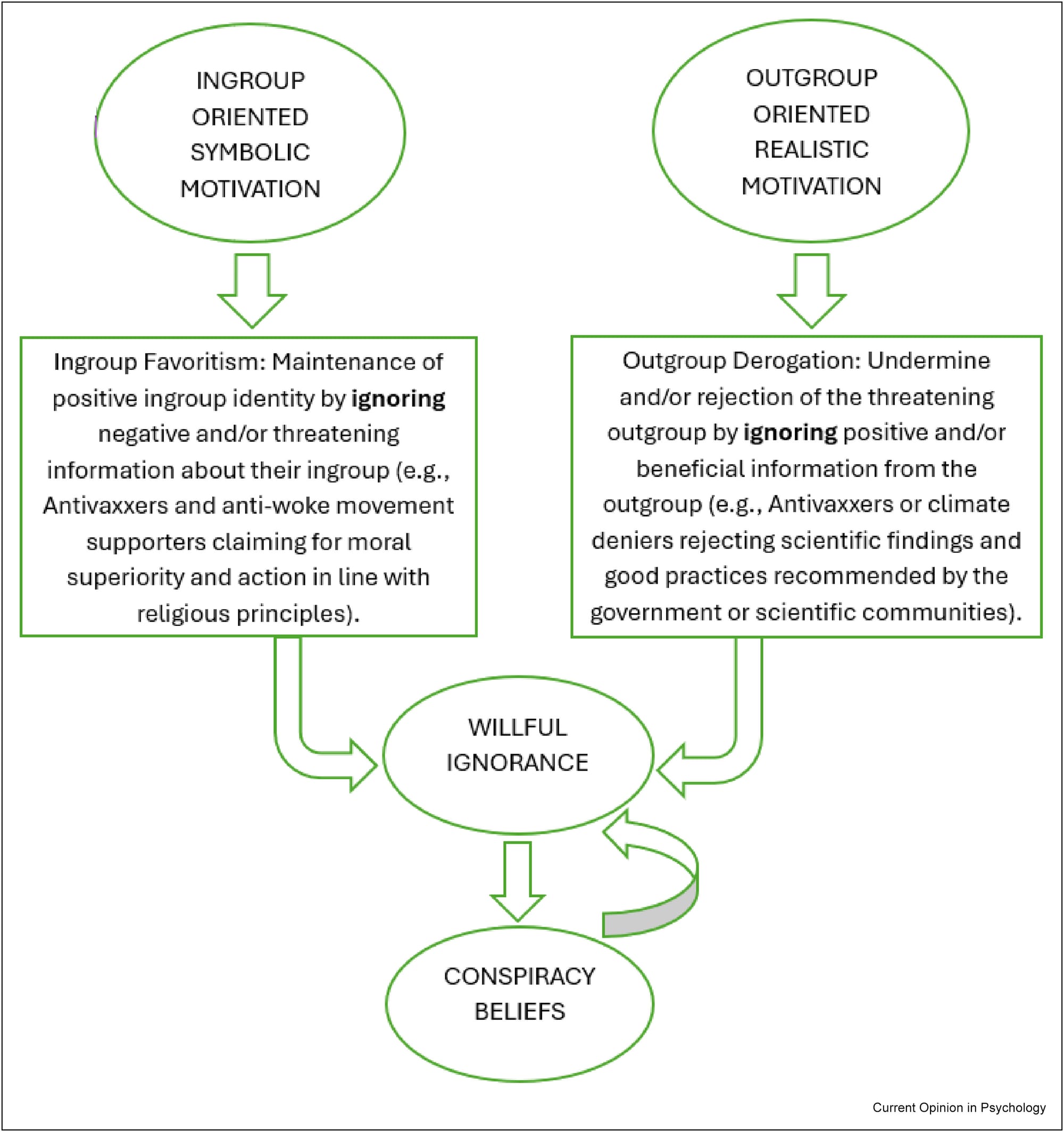

We tend to process information through "cultural cognition." We align our beliefs with the groups we identify with. If my social circle believes that climate change is a hoax or that a specific geopolitical group is inherently evil, I am socially incentivized to reject facts that contradict that view. The facts aren't fighting ignorance; they are fighting identity.

A Case Study: The EV Efficiency Argument

Let’s look closely at that electric car argument, as it perfectly illustrates this disconnect.

The common claim is that the US grid is dirty, so EVs are dirty. Here is the reality we can measure:

- The Grid is Changing: As of 2024, renewable energy sources like wind and solar have actually overtaken coal in the United States. Coal now accounts for roughly 16% of total electricity generation, while natural gas is around 43%. The idea that the grid is "mostly coal" is a relic of the past.

- Thermodynamics Wins: Even if you did charge an EV 100% from coal (which is rare), it would still likely be cleaner than a gas car. A massive power plant is incredibly efficient at turning fuel into energy compared to the small, inefficient explosion engine in a Toyota Camry.

When we measure awareness here, we often find that people are operating on data from 20 years ago. They aren't necessarily "anti-science"; they just possess an outdated mental map of the world.

Addition note; this also all depends on where you charge. If you charge in a fossil fuel heavy area (like Indonesia, China, or Wyoming), you will get similar to slightly worse emissions for EVs. But if you have renewable energy set up with better grid infrastructure, emissions will significantly lower emissions. But all this comes from awareness and knowledge and investigation. Finding those nuances help us move forward instead of disposing ideas without giving them second thoughts.

Forecasting the Future of Truth

If we look at current patterns, the divide in public awareness is likely to widen before it narrows. Algorithms on social media platforms are designed to feed us content that engages us, not content that educates us. This creates "reality tunnels" where two neighbors can live in the same city but exist in completely different worlds of fact.

However, I see a potential shift. We are reaching a saturation point with misinformation. Just as we eventually developed spam filters for our email, I predict we will see the rise of "verification tools" integrated directly into our browsers and news feeds—systems that give real-time context to claims (like the "Community Notes" feature we see on X).

How to Gauge Your Own Circle

So, how do you measure awareness in your own life without starting a fight?

Instead of asking, "Did you know X?", try asking, "How do you think X works?” Just don’t ask it all sneezy or know-it-all like. Ask it with genuine curiousity. Sometimes (especially with my conversations) I learn something new or see a different perspective.

This is a technique used by cognitive psychologists. When you ask someone to explain the mechanism of a problem—how a bill becomes a law, how a battery stores energy, or the history of the conflict in Gaza—they often realize the gaps in their own understanding. It moves the conversation from "My Team vs. Your Team" to a shared exploration of mechanics.

The Path Forward

We cannot force people to learn, but we can make accurate information more "sticky" than the lies. We need to stop treating knowledge as a lecture and start treating it as a story. When we talk about climate change, we shouldn't just talk about degrees of warming; we should talk about the stability of the insurance market or the price of coffee. We have to connect the abstract data to the tangible reality of daily life.

I’m curious to hear from you. Have you ever had a moment where you realized you were operating on outdated information? Or have you found a specific way to get through to friends who seem stuck in a different reality?

Tell me your story in the comments below.

- US Electricity 2025 Special Report (Ember Energy)

- US Energy Information Administration (EIA) FAQ on Electricity Generation

- Emissions Associated with Electrical Vehicle Charging

- Seven Key Gallup Findings About the Environment (Gallup)

- Public awareness of science (Wikipedia)

- Why facts don't change minds (LSE Blogs)

- Agnotology

- A community of unknowledge

Comments ()